Dearest readers,

It’s been a while since I wrote last. There’ve been two recent deaths in my family. Two women who shaped me with their unwavering love have left this earthly plane.

For paid subs, you will get 2 x meditations this month in your inbox (one for last month).

This is a personal essay about my last days with my stepmother.

It’s a ‘when the kids are in bed’ kinda post. X

As I sat next to her bed in the hospice, she looked at me and said, “I can’t tell you what it means to me that you came.”

I’d taken a last minute trip from Australia, leaving my daughter, Gia, for the first time at home with her dad. Something told me the prognosis of a few weeks to live was wrong and I needed to get to UK asap if I wanted to say goodbye to my stepmother.

I held her hand and cried with the relief that I’d made it.

My dad texted me before I flew to tell me that B kept saying, “I can’t believe Sarina’s coming. I’m so thrilled she’s coming.”

It made me confront how she’s doubted her place in my heart and my life.

“I came because I wanted to do this.” I gently lifted the frail hand I was holding. “I wanted to look you in the eyes and tell you how much I love you.”

She held my gaze and I could feel her whole body wrapping itself around my words; the first time I’d shared such words, the first time she was ready to receive them.

How had my stepmother and I shared four decades together and never before exchanged these words?

Because herself, as a woman in her mid-thirties, pained from her unmothered, unfathered childhood, entered a relationship with a man who had two children he adored, while accepting she would never come first.

And myself, as a four year old child, was protective of my dad and probably confused and conflicted by this wonderfully kind woman coming into my world, while having to share my already limited time with my father.

From the beginning, my stepmother and I were cautious.

Over four decades, the familiarity and care for each other grew, but caution remained. The tone had been set from those awkward first years, and somehow it became too vulnerable to express the love we actually held in our hearts.

That is, until it was our final goodbye.

Nicolas Roshylo Unsplash

A few hours before landing into Heathrow, I felt overwhelmed about what was ahead. Did I even have capacity to support my dad and my sister’s grief? Would there even be space for my own grief? My dad was losing his wife of 36 years and my sister was losing her mum. Where was my place in all of this?

Thirty-odd thousand feet in the air, I was suspended between two worlds, one where I am a mother and partner and the other where I’m a daughter, stepdaughter and sister. In these final hours before touchdown I realised how rare this moment was; I wasn’t needed by anyone. I had the space to get really fucking clear on God’s will* for this one heartbreaking week in UK.

Memories flashed in my mind of the time before my sister was born, just before I turned nine. How I’d been antagonistic and hostile toward B, and then how I would flip on a dime and soften into her care and compassion. She was always concerned for how hard this was for me. That’s the thing about B, she was selfless, practically to a fault.

She’d often stay in the car with a thick book she was reading, insisting she was happy to let my dad have time alone with his kids at the zoo or the swimming pool or the park.

I’d look back at the car as my brother and I walked away with our dad and wonder, “Why doesn’t she come with us?” I probably asked my dad this. He probably said she preferred to read her book. But something in me knew she was setting herself aside, getting out of the way. Something in me felt this isn’t right.

Two hours before touchdown, I pulled out my journal and furiously wrote my way through the headfuckery of ‘I don’t even know my place in all this. Am I meant to be a support role? Can I let myself surrender to the sorrow of losing the woman who’d become a figure of kindness, compassion and generosity, and then who’d become the adoring ‘Nana’ to my daughter?’

The scrawling words across the page revealed, here I was, ‘doing a B’, wondering if I belong, wondering if my love has a place, wondering if my authenticity and needs were appropriate.

I wrote my way through the dark squeeze of my thoughts and into the open where I could see, God’s will for me was simply to be of service to What’s Most Needed. To be attuned to What’s Most Needed in any given moment.

Relief washed through me. Within this intention to attune to What’s Most Needed, everything has its rightful place. - the support for my dad and sister, in listening and holding, cooking and cleaning, and, feeling the overwhelming sadness of losing B.

My journal now held the most poignant intention I’d probably ever set. To be attuned to What’s Most Needed, from the very moment I was to see my dad waiting for me at the exit gate.

Dad and B’s house is filled with large crystals and fossils, copper sculptures of T3 viruses - my dad’s particular obsession, and B’s wall art pieces, such as three fish made from recycled materials she found along the shorelines in UK.

A visitor once asked if she could buy the fish, one of which had a body fashioned from the sole of a battered leather shoe. B couldn’t believe anyone would want to buy it. She didn’t consider herself an artist and was convinced the visitor offered to buy it because she wanted to be ‘nice’.

It broke my heart to hear this story from my dad, whose encouragement and gushing love for his wife’s art did little to soothe her sense of unworthiness.

Yet, when I would share my latest artwork in our family WhatsApp group, B was always the first to celebrate and congratulate me.

When I arrived in UK last year with Gia, I noticed a series of small artworks on the mantelpiece, each one an entire frame of colourful squares within other squares, one piece in lilac, violet and mauve with gold outlines, others in green, yellow and ochre.

“What are these?” I asked.

“B did them.” My dad said. “Aren’t they gorgeous?”

“B, these are AMAZING!”

She beamed. “Oh, I’m so glad you like them.”

My eye scanned across the four pieces, barely able to land on a favourite, they were all so striking.

They started as a doodle, she told me. While waiting for dad to make his Scrabble move, which notoriously could take up to an hour. She’d usually beat him anyway, but this was her way of redirecting the frustration of just sitting there, waiting for her turn.

B was an artist. She made art that delighted people. She made art that made me proud to belong to her and to their home.

A couple of years ago, my dad posted some pictures of his and B’s artwork in the family group. I messaged back how inspiring and wonderful it is to have such a creative family. I’m realising it more fully now - B couldn’t entirely receive these words.

Her default was to see her art as silly, nothing worthy of recognition. Still, there were bursts of artistic expression. It’s like the muse was more powerful than her sense of unworthiness.

My sister arrived at the house while I was in the shower. I insisted on ridding myself of the ‘plane germs’ before heading to the hospice.

I came out of the bathroom wrapped in a towel, with sopping wet hair, and when my sister and I saw each other, there was a look. No words were needed. I held her and my dad wrapped his arms around us both.

How could I have doubted what I was here to do? How could I have doubted how Love would guide me? How is it that we objectify not only people but our place in the world?

I was nervous though. I was nervous to see how thin B had become, how ill she was. I was scared to be immersed in the reality my dad and sister had been in for the past few weeks since B was in excruciating abdominal pain.

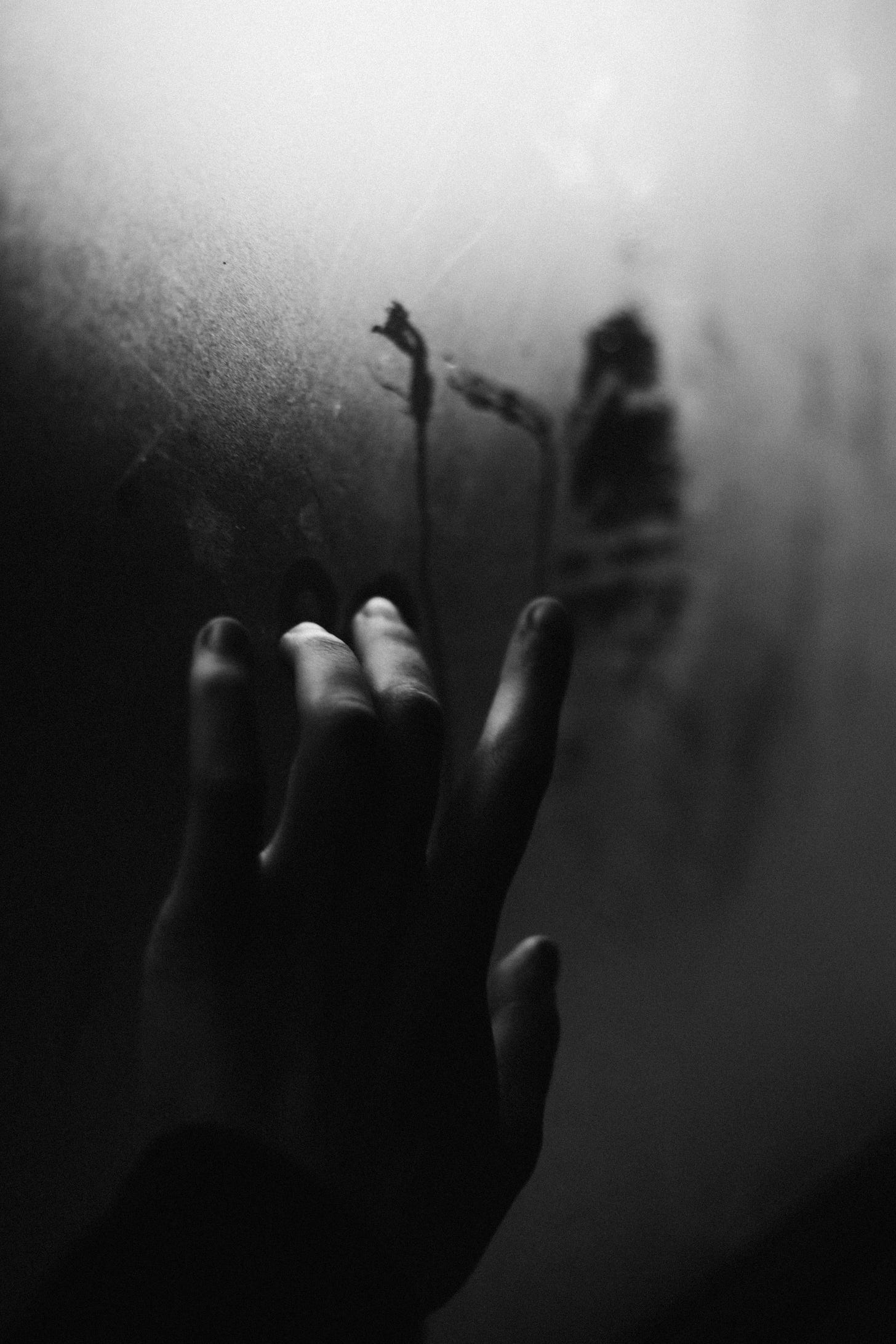

More so, I was nervous to confront what had remained unspoken between us. To confront the love I’d held back for almost forty years.

And then, there I was at her bedside, holding her hand, losing all composure to sorrow. Letting her see how much she meant to me. I was unfamiliar to myself, exposed, heartbroken, vulnerable.

What’s Most Needed, in this moment, was this. The full expression of my sadness.

Her grey-green eyes met me more deeply than ever before. She wasn’t afraid now.

I moved closer and sat on the edge of the bed. B’s hand reached for my damp cheek. “Oh, darling.”

This is what it felt like, to surrender to each other’s love.

Each morning before we got in the car, we picked sweet pea flowers from the garden, one of B’s favourites. Pale purple-blue, white, magenta. I looked at them with the sadness of knowing how they’d remind me of her. She was always enchanted by how fragrant and delicate they were.

B was a lifelong collector of 1930s and 1940s glassware and crockery. For the sheer joy, she’d scour car boot sales for treasures and occasionally have her own stall, alongside her best friend, at an antiques fair, although she could barely bring herself to charge more than she paid for each piece.

A small 1930s glass vase sat on the trolley table that hovered over B’s bed, bursting with sweet peas, a thing of beauty among the bottles and packets of medications.

Gia’s painting of two red flowers for her Nana, framed by my dad, stood on the cabinet under the TV next to more flowers from B’s friends.

At times, when B needed to rest in quiet, we’d take our packed lunches outside the double-glazed French doors to the cast iron tables and chairs, where a robin red breast came to sit with us, often just a foot away, tilting its head, as if to say, “Are you ok?”

We offered it tiny crumbs of our food, but it wasn’t interested in the food. It just looked at us, hopping from the top of a chair to the arm of the chair and then to the seat. It would stay with us for several minutes at a time, and occasionally hop onto the floor and peek through the doors toward the bed, as if to offer B its blessings.

We were all convinced this was my Nana, my dad’s mum, who’d passed a few weeks ago at 99 years old. She had such love for the robins that would come drink from the birdbath in her garden. “Oh look dears, the robin!” It gave her such delight and each one of us grandchildren shared this delight, such a delicate, handsome bird, always alone, always visiting in the most peaceful moments.

My dad, sister and I gathered these sticks from a woodland near the hospice and wove yarn and beads around them one sunny afternoon outside B’s room, the robin was keen to watch, and it was B’s last time joining us around a table. She sat in her wheelchair, her eyes mostly closed, listening to Franco Luambo music we played for her. It brought all of us joy to be quietly creating something, no pressure for B to engage, just a time for her to enjoy being surrounded by family, enjoying some last peaceful moments all together. Exactly What Was Needed.

One week later, it was my final goodbye with B before heading home.

She was weaker now and her eyes stayed mostly closed during our visit.

Over the past few days I’d held B’s hand for long periods as she tightly gripped mine back, despite her body’s weakness.

I’d shared how grateful I was for her grace and compassion and care for me, and with every word I uttered, we both healed.

The grief of losing B was something I needed to face, but I was determined that neither she nor I would die with the grief of unspoken words.

Each of the days at the hospice, I made sure B knew, with my gestures and my words, that I cherished her.

My sister asked if I wanted time alone with her mum. I told her to stay, knowing that every minute with her mum was precious. But when I moved over to the bed and took B’s hand for the last time and told her, “I’m going to say goodbye now,” I noticed my sister quietly leaving the room.

My sister was offering me my place, intuitively acknowledging What’s Most Needed, and that although I wasn’t losing my own mother, it mattered that I was losing someone so dear to me.

The opiates were causing her legs to jerk as well as occasional hallucinations. As I perched on the bed next to her, B kicked her legs under the blankets. “Ooo there’s a snake in the bed or something.” Then she giggled, realising her mind was playing tricks.

“Oh no, we don’t want snakes in the bed!” I said.

“No, no,” she smiled and opened her eyes to look at me.

I leaned over her, careful not to disturb the syringe driver, and wrapped my arm under her sharp shoulder blades.

“We did well, didn’t we?” She said quietly.

“We sure did.” I knew exactly what she meant.

“I never wanted to take your dad away from you or replace your mum, and when [my sister] came along I never wanted you to feel like we were a unit with your dad and you two were outsiders.”

I told her I’d always sensed her putting us first; to the nth degree. And that, sometimes - remembering her reading those thick books in the car on her own, that I didn’t even want her to put us first.

She gently nodded, understanding that she had always had a welcome place in our lives, even through those early years where I was sometimes hostile.

“It was amazing that you could do this, B, that you could be so devoted to this, when it was never modelled to you.” Her own stepmother had shut B and her sister out, and her father had never insisted on including them. “It’s truly amazing. Thank you. Thank you for being my stepmum - I never even liked the word stepmum.”

“No, it sort of has not nice connotations, does it?”

“Second mum. Thank you for being my second mum!”

She smiled.

“And thank you for being my —“ She trailed off.

“First-second daughter?” I suggested.

“Yes.” We laughed.

Some moments passed as she continued to hold my gaze.

“We’ll meet again,” She assured me.

“Oh, yes, I know it. I love you. Go gently.”

“I love you. I will.”

I kissed all over her face, her cracked lips and hollowed cheeks. She kissed me back, her lips struggling to pucker, but she mustered the energy to move her face all around mine too.

Her tight grip on my hand loosened.

It took almost forty years, but we finally surrendered into the fullest expression of love, and let each other go in the knowing that nothing beautiful was left unsaid.

I’m so grateful it wasn’t too late.

What an incredibly moving post, Sarina. Thank you for sharing it with us. I wish your family gentle love and healing in this time of goodbyes for now. Xx

This line will stick with me for a while: “… the muse was more powerful than her sense of unworthiness.”

Your beautiful words have brought tears to my eyes. I’m sorry you lost your stepmum but so happy for both of you that you got to say what’s most needed.